The Innovation-Adoption Curve

The Innovation-Adoption Curve is a graphical representation of Diffusion of Innovations (1962), a model created by Ohio State professor Everett Rogers as a method of explaining how, why, and the rate at which an innovation spreads through a population or social system. An innovation is a product, service, or idea that is perceived as new by its audience.

The Diffusion of Innovations model and the innovation-adoption curve offer three valuable insights into the process of commercialization:

- What qualities make an innovation spread successfully.

- The importance of peer-to-peer networks.

- Understanding the needs of each adoption segment.

These insights have been tested in more than 6000 research studies and field tests, so this is probably the most reliable model in the field of technology and innovation adoption.

The Innovation-Adoption Curve has spawned a range of adaptations that extend the concept or apply it to specific domains of interest, such as a model specifically for technology-based products.

Overcoming barriers to innovation adoption

The Innovation-Adoption Curve, as described in Diffusion of Innovations, takes a very different approach to describing change than most other behavioral theories. Instead of focusing on persuading individuals to change, it describes change as being caused by the evolution or “reinvention” of products and services, so they become a better fit for the needs of individuals and groups. In Diffusion of Innovations, it is not people who change, but the innovations themselves.

Why do certain innovations spread more quickly than others? And why do others fail? Rogers and his colleagues identified five qualities that determine the success of an innovation:

1) Relative advantage

Relative advantage is the extent to which an idea or product is perceived as better than the method in current practice. The greater the improvement — as measured by a particular group of users in terms that matter to those users — the greater the chance of adoption.

2) Compatibility

This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with existing values and practices. An innovation that is compatible with the values, past experiences, and practices of potential adopters will be adopted rapidly.

3) Complexity

This is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use. New ideas that are simpler to understand are adopted more rapidly than innovations that require the adopter to develop new skills and behaviors.

4) Trialability

This is the degree to which an innovation can be experimented with on a limited basis. An innovation that is “trialable” represents less uncertainty and lower risk to the individual who is considering it.

5) Observability

The easier it is for individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt it. Visible results lower uncertainty and also stimulate peer discussion of a new idea, as friends and neighbors of an adopter often request information about it.

According to Everett Rogers, these five qualities determine between 49 and 87 percent of the variation in the adoption of new products. These five qualities can help identify weaknesses is your product offering and/or the perception of high risk in your business activities.

Innovation Adoption is Based on Reinvention

Reinvention is the primary concept in Diffusion of Innovations. The success of an innovation depends on how well it evolves to meet the needs of more and more demanding and risk-averse individuals in a population.

A good way to achieve this is to continuously encourage users to help you with the process of redevelopment. Many successful companies seek to make users active partners in the reinvention process, by supporting user communities or by applying participative research techniques.

In the gaming industry for example, end users are actually participating in the design of the game. Instead of complaining, they help fix the product. The concept of reinvention is important because it tells us that no product or process is ever completely finished — continuous improvement is the key to spreading an innovation.

The importance of peer-to-peer networks

The second important insight is that impersonal marketing methods like advertising and storytelling may spread information about new innovations, but it is conversations that spread adoption.

This is because the adoption of new products or behaviors involves the management of risk and uncertainty. It’s usually only people we personally know and trust – and who we know have successfully adopted the innovation themselves – who can give us credible reassurances that our attempts to change won’t result in embarrassment, humiliation, financial loss or wasted time.

Early adopters are the exception to this rule. They are on the lookout for advantages and tend to see the risks as low because they are comfortable with high-risk propositions and unproven innovations. Many times, an early adopter will embrace an innovation on the basis of nothing more than a well-worded scientific paper or news article. The rest of the population, however, see high risks in change, and therefore require assurance from trusted peers that an innovation is adoptable and provides predictable benefits.

As an innovation spreads from early adopters to the mainstream early majority, face-to-face communication becomes more essential to the decision to adopt. Rogers notes that by 2003 there had been eight randomized controlled trials – the gold standard in evaluation – all of which demonstrated the ability of opinion leaders in peer groups to produce behavioral change.

Understanding the needs of different user segments

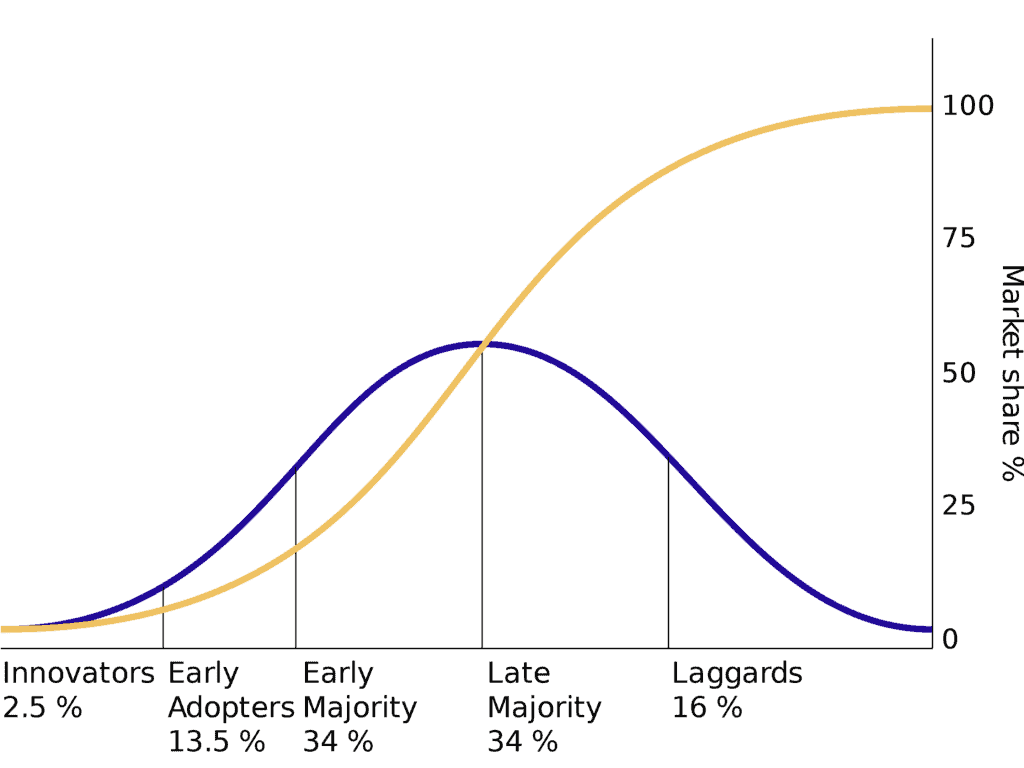

Rogers’ diffusion model, as represented by the Innovation-Adoption Curve, indicates that a population can be broken down into five different segments, based on their aversion to risk and propensity to adopt a specific innovation: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. Each group has its own “personality.”

When thinking about these groups, it is incorrect to try to shift people from one segment to another. It’s best to think of the characteristics of each segment as static. Innovative new products spread when they evolve to meet the needs of successive segments.

Innovators

Innovators are adventurous and willing to take risks. They fundamentally want to be the first to try new things. Their goal is to explore new technologies or innovations and find opportunities to be an agent of change. Innovation is a central interest in their life, regardless of what function it is performing. Unfortunately, this fixation with new products and ideas can make them seem dangerous to the mainstream majority. There are not very many innovators in any given market segment, but winning them over at the beginning is important, because their endorsement reassures the other people in the marketplace that the product does in fact work.

Early Adopters

Once the benefits of a new innovation start to become apparent, early adopters leap in. Early adopters buy new technology to achieve a revolutionary breakthrough that will give them a dramatic competitive advantage in their industry. They love getting an advantage over their peers and they seem to have time and money to invest. They become an independent test bed, identifying the rough spots and reinventing the innovation to suit mainstream requirements.

Early Majority

The mainstream early majority typically values innovations that solve a specific problem. They look for complete products that are fully tested, adhere to industry standards, and are used by others they know in their industry. They are looking for incremental, proven ways of doing what they already do. They require guaranteed off-the-shelf performance, minimum disruption, minimum commitment of time, minimum learning, and either cost neutrality or rapid payback periods. And they hate complexity. Because there are so many people in this segment—roughly one-third of the whole adoption life cycle—winning their business is key to any sustained profits and growth.

Late Majority

The late majority is risk averse and only adopts new innovations to avoid the embarrassment of being left behind. Change is unsettling to this group so they look for high levels of support and standards certification. Like the early majority, this group comprises about one-third of the total buying population in any given segment. Serving this segment correctly leads to an ongoing source of sustained profitability. Even though profit margins decrease as the products mature, so do selling costs, and virtually all the research and development costs have been amortized.

Laggards

Laggards hold out to the bitter end. They value traditional methods of doing things and refuse to adopt a new technology until they are forced to through obsolescence of their former system. The only time they ever buy a new product is when their traditional way of doing something has failed and cannot be repaired. Laggards are very skeptical of change and are the hardest group to bring on board.

Each of these adopter types has a very different personality. And it’s vital to know which one you are addressing at a given time. However, because the Innovation-Adoption Curve is based on human characteristics such as reasons, opinions, and motivations, it is impossible to identify the precise transition point between segments.

When introducing a new product or service, you need to know one vital fact: the percentage of people who have already taken up the innovation. That figure tells you which adopter segment you will be addressing next.

Also keep in mind that a given person is not necessarily a specific adopter type in all situations. In other words, a person might be an early adopter of mechanical innovations, but a late adopter of biological innovations.

This is why you will never identify an early adopter with a survey or through an online questionnaire. The past behavior of an early adopter means nothing in terms of future behavior.