Meet the original creators of the chasm concept

Crossing the Chasm Summary: For every innovative product, strategy or idea there are pioneers or originators who aren’t recognized or acknowledged as the true creators of that innovation. For example, laptop and mobile computers are everywhere these days, but very few people remember that Adam Osborne was the original creator of the first portable computer.

The same thing is true for a market-development framework that is widely discussed in Silicon Valley, known as Crossing the Chasm.

The Chasm concept was first developed by Lee James and Warren Schirtzinger, founder of High Tech Strategies. Both gentlemen worked for the high-tech consultancy Regis McKenna Inc. (RMI) in the Pacific Northwest.

Technology Adoption Foundation

This Crossing the Chasm Summary proves the chasm concept itself was first used as a market strategy in 1989 by Lee R. James and Warren Schirtzinger who were consultants at Regis McKenna Inc. [Note: Lee James was also the person who created the Right Turn on Red Law while working at the Federal Energy Administration during the 1970s oil crisis, using his innovation-adoption skills to encourage conservation.]

It all started when the two colleagues noticed that high-tech products don’t follow the same pattern of adoption as other non-technical products. They observed that high tech products often struggle to gain mainstream acceptance, and even fail, even though they are initially well received. The products attract great interest and have early success—then they stall out.

Later, James and Schirtzinger identified the point of greatest difficulty in the development of a high-tech market as a transition from an early market, dominated by early adopters to a mainstream market dominated by a large group of customers who are realistic and practical. Together they decided to label this phenomenon “the marketing chasm,” and the framework was used extensively by RMI consultants in the Pacific Northwest.

Client engagement documents, such as this one prepared for PaineWebber by Geoff Moore in 1990 (who was an RMI consultant in California) proves he was writing a book called “High Tech Marketing, Changes in the Game,” but had yet to learn about or use our chasm theory. When introduced to our “marketing chasm” framework and the theory behind it, Moore renamed his book and popularized what has become known as “Crossing the Chasm.”

This Crossing the Chasm Summary presents internal documents and faxes from Regis McKenna Inc. that show Mr. James and Mr. Schirtzinger were using the chasm framework in client engagements in early 1989…over two years before a book by the same name was first published.

For More Information:

Please read the “Concept Formation” study conducted by The Diffusion Research Institute that provides a detailed history of how the Technology Adoption Lifecycle and Crossing the Chasm models were initially developed:

Crossing the Chasm Summary

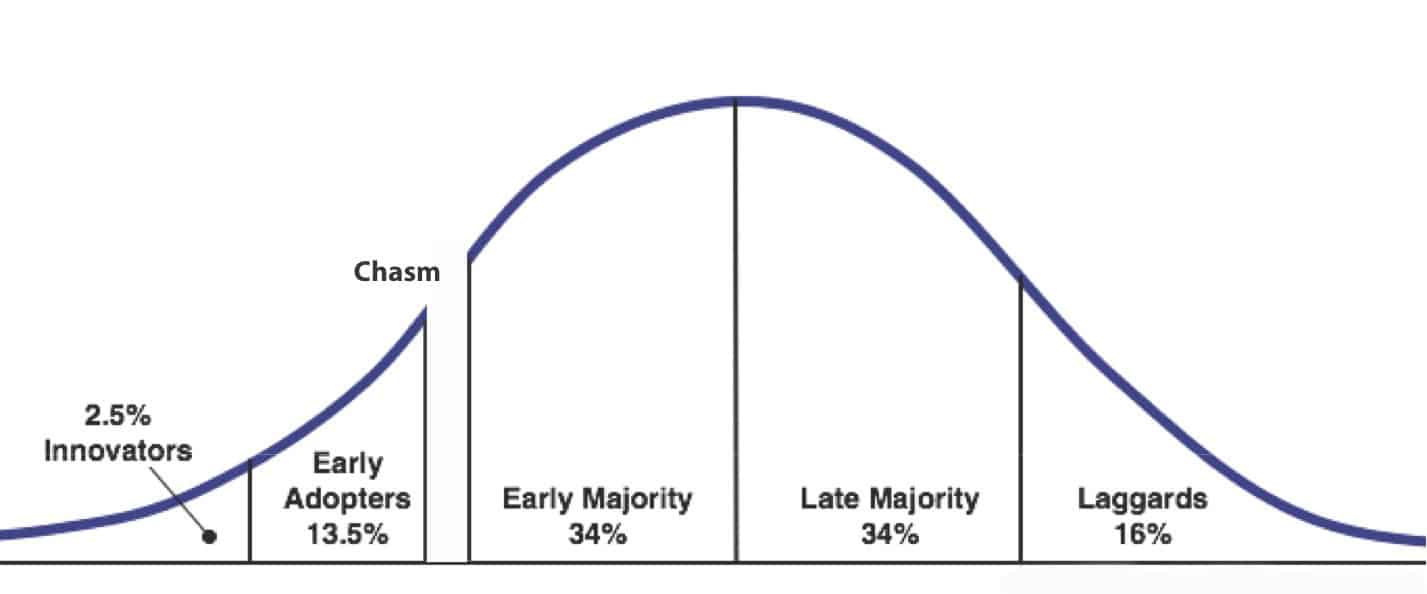

Crossing the Chasm is an adaptation of a market development model called Diffusion of Innovations. The underlying thesis of the Diffusion of Innovations model is that innovations are absorbed into any given user base in stages corresponding to psychological and social profiles of segments within that user community. The process can be represented by a bell curve with definable stages; each associated with a definable group, and each group making up a predictable portion of the whole community.

Sometimes referred to as the Technology Adoption Lifecycle, it is a model that describes a market’s acceptance of a new product in terms of the types of consumers it attracts throughout its useful life. It is probably the most well established model in “new product marketing” because it provides useful insight at all stages of market development.

The prescription for success in introducing a new product or technology into any community is to work the curve from left to right, focusing first on the innovators, growing that market, then moving on to the early adopters, growing that market, and so on. To do this effectively, it is necessary to know and understand the psychological characteristics of each group of buyers. This sequence of adopter types is the foundation of Diffusion of Innovations and also the primary message in this Crossing the Chasm Summary.

Adaptation of Diffusion Theory

Diffusion of Innovations and Chasm theory both seek to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technologies are adopted. It is fundamentally a study of the psychological characteristics of buyers.

Whereas the technology adoption lifecycle implies a smooth transition from early adopters to the early majority, James and Schirtzinger discovered that instead of that being a graceful transition, there was actually a gap — because early adopters have very different values and motivations than people in the mainstream. And many of the tactics that initially lead to success in the early market, will work against you in the mainstream market.

Moving from early adopters to the mainstream early majority requires a complete shift in focus. The key to this shift in focus is moving from a technology orientation to a people/human orientation. And many of the things that made you successful in the first part of the market will cause failure in the mainstream market. It will be necessary to change your: value proposition, marketing, product focus, distribution, positioning messages, and communications.

Diffusion of Innovations Psychographics

The psychographics of each group in the adoption process influences the development and dynamics of the market. For example, each group places a different value on product intangibles, and on endorsements or references from other groups. As products move through the adoption process, intangibles and user references assume more importance. Often, pioneering new products lose their initial prominence because a new entrant is more successful in product positioning based on a more effective mix of intangibles. This can be the case even if the second product is not technically superior.

The concept of dynamic change in the perceptions of products is reinforced by the concept of the adoption process. In 1957, researchers at Iowa State College were able to track the diffusion of information and purchase patterns of a new product: hybrid seed corn. They found that purchase and use (or adoption) behavior fell into understandable patterns. They found that five “segments” of an adoption population could be described. They noted the different characteristics of persons in these five groups, and hypothesized about the way word-of-mouth influences purchase behavior.

Five groups were identified as follows:

• Innovators–2.5% of the population

• Early Adopters–13.5%

• Early Majority–34%

• Late Adopters–34%

• Laggards–16%

The research demonstrated a number of elements of purchase behavior, including the dynamic nature of how products are purchased. Innovators, for example, are motivated by being first, while late adopters are primarily interested in a bullet-proof product.

The primary value of the research was the development of the idea of a “diffusion process.” New product acceptance could finally be understood and even diagramed.

Crossing the Chasm Weaknesses

In addition to the misunderstandings created by crossing the chasm, there are three areas where Moore’s book does not fully communicate the critical information that is often needed. And those who use Crossing the Chasm as their primary guide for finding a scaleable business model, risk making these known mistakes. The three areas are:

1. An innovation can be both continuous and discontinuous

Other than confusing the difference between “disruptive” and “discontinuous,” the most common misunderstanding among people who read Crossing the Chasm is they tend to believe that all markets and populations have a chasm. But as you know, the chasm only applies to “discontinuous innovations” and does NOT offer useful guidance for continuous innovations. This distinction is not presented with enough detail in Moore’s book, and the key to differentiating the two types of innovation requires more than looking for a change in behavior. The degree of discontinuity is also influenced by the ability of an industry or population to learn new things.

This is one of the fundamental misrepresentations in the book Crossing the Chasm. Not all industries or social systems learn at the same rate. Whereas an innovation might be a continuous innovation in one sector or geographical area, it might be a discontinuous innovation in different geographical areas or cultures or industries, because learning new things is more difficult for some populations. Crossing the Chasm does not discuss the potential duality inherent in some innovations.

2. The characteristics of early adopters are much more variable and complex than described

Crossing the Chasm describes early adopters as a rare breed of visionaries “who have the insight to match an emerging technology to a strategic opportunity.” And a lot of attention in the book is focused on the single characteristic found in all early adopters which is the desire to find a fundamental breakthrough or gain strategic advantage. This sets up the primary theme of the book which is the chasm exists because the buying criteria and performance expectations of early adopters are dramatically different than those for the early majority.

What I’ve discovered in doing my own research and in the research of others is early adopters are not always easy to characterize, AND there are certain market dynamics that completely nullify these assumed characteristics.

One industry where this is common and easy to see is solar power and renewable energy. The earliest buyers of solar in many locations are not technology enthusiasts or visionaries, but rather pragmatic consumers who buy for ethical reasons. But even more dramatic in terms of chasm nullification are the subsidies and government incentives that often accompany solar power.

The adoption-skewing effect caused by government subsidies can be so dramatic, you will find early adopters who are not visionary at all but more closely resemble the late majority. This also explains why the use of references and referrals among early adopters is often ineffective. Many of the fundamental personality differences found among early adopters make it so they don’t like each other. And a reference from one type of early adopter will actually repel other types of early adopters.

3. The chasm model fails in the area entrepreneurs and product leaders need most

Using a “D-Day analogy” Crossing the Chasm tells managers to marshal all available resources in collaboration with selected partners/allies and create a minimum viable [whole] product that meets the target customer’s compelling reason to buy, thereby establishing a foothold in a niche segment of the mainstream market.

Unfortunately this prescription does not help address the number one challenge faced by most emerging high tech companies. For entrepreneurs and managers alike, the primary question to answer is: how much of our limited resources should be allocated to the products/services we offer today, and how much should be allocated to the products/services we want to offer in the future?

Obviously, this is not a critical question for startups with just one product. But managers of companies with an existing product recognize that every resource allocated to a new product could, in the short term, be allocated to the success of an existing product. And for new products or innovations there is no real way to predict return on investment. Crossing the Chasm does not provide a useful answer to this fundamental question….or even worse, it encourages managers to wait until the chasm to truly invest in the needs of mainstream customers.