No technology is born ready to serve every use case. And the technologies behind clean energy innovation take time to develop and mature. But in the rush to acquire customers, it’s easy to shortchange the critical step of finding the right applications and segments for a startup’s technology. This can slow company growth, burn precious cash, and ultimately jeopardize the venture’s existence.

When executed well, the search for best-fit use cases creates financial and market momentum, giving the startup time to expand its technology and pursue additional opportunity. While successful innovations look obvious in retrospect, they often struggle to find product/market fit initially, making this focus vital.

To illustrate how the square hole approach can drive success, consider some well-known examples from beyond clean energy:

In 1999, most consumers weren’t interested in a digital wallet and payment system, due to security and fraud concerns. But those who embraced ecommerce early – like eBay users – were already suffering with the time lag and security risks of sending checks or credit card numbers to strangers. They embraced a faster and more secure service, enabling PayPal’s astronomical growth. If instead PayPal had doggedly pursued the broader consumer market early on, would they have caught fire before running out of cash?

In 2006, taking on Ticketmaster as a tiny startup would have been foolhardy. But there was a huge unserved market for event ticketing that didn’t require advanced features or massive scalability, and which couldn’t afford Ticketmaster’s fees. From yoga seminars to food festivals, small events fueled the rise of Eventbrite, which over time expanded its product to address even more use cases. By not trying to outcompete Ticketmaster in its core market, Eventbrite found a niche that it built into an attractive new market.

Introducing the Square Hole Approach to Clean Energy Innovation

The drawbacks of new technologies don’t have to be blockers. Instead, they can be motivation to think creatively and dig deeper for the right use cases. We call this the square hole approach: rather than forcing square pegs into round holes, find the square holes where they fit beautifully. This means identifying niche markets where your technology’s strengths align perfectly with customer needs, and where its limitations don’t hinder its success.

The fact that an initial use case or market is limited in size doesn’t shut off larger market opportunities in the future. Often the company can apply a “domino” approach and penetrate additional markets/applications as the technology matures – while benefiting from early tailwinds of cash flow, satisfied customers, and positive reputation.

Learning from Square Hole Success Stories

In the clean energy space, hardware innovations often have significant drawbacks early on. But savvy entrepreneurs have overcome those limitations and found attractive market segments that helped them build thriving businesses. Let’s look at some examples that can provide insight and inspiration for today’s startups.

Solar panels for off-grid facilities: Applied Power Corporation

Before PV systems became the ubiquitous low-cost workhorse we know today, they were an expensive technology trying to drive cost down along the experience curve for decades. While solar modules now sell for <$0.10/W in China and $0.29/W in the US, they cost a whopping $10/W in 1992 [1, 2]. This made them economically infeasible for most applications.

But as with Eventbrite, there were unserved markets that could ultimately prove lucrative. Where did unserved electricity demand exist in the 1990s? Remote locations like national parks had off-grid facilities that were a perfect match for PV systems. Solar panels may have been prohibitively expensive by today’s standards, but the willingness-to-pay was quite high in places that couldn’t access grid electricity. Applied Power Corporation served this niche beautifully, which ultimately contributed to its successful acquisition by IDACORP in 1996.

Thin-film cadmium telluride (CdTe) solar panels: First Solar

PV technology has become almost synonymous with silicon, but there’s another type of PV tech that’s been making inroads for years. Thin-film cadmium telluride (CdTe) technology was first developed in the 1950s/1960s and commercially pioneered in the early 2000s by First Solar, which remains the CdTe leader today. This technology has two major drawbacks relative to silicon PV cells: lower efficiency and environmental/health risks stemming from cadmium, a toxic metal.

With efficiency being critical, CdTe’s disadvantage would seem tough to overcome. Greater efficiency yields more electricity produced per area of solar cell. This matters a lot if you’re putting solar panels on a residential or commercial roof with limited area. But for applications like utility-scale solar, the price per Watt matters more than PV cell efficiency, and on that dimension the performance difference is narrower between the technologies, with CdTe sometimes holding the advantage. CdTe also performs better than crystalline silicon in high temperatures, making it an ideal technology for large-scale solar deployments in hot locations.

These advantages have led CdTe to capture 40% of the US utility-scale PV market and 5% of the global market [3], with First Solar becoming a $3 billion revenue company in the process.

Solid oxide fuel cells: Bloom Energy

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) are another technology that’s been around for decades and reached meaningful adoption in the last 15 years. They produce reliable, continuous electricity via modular equipment deployed on-site where power is needed. SOFCs convert a fuel (typically natural gas), oxygen, and steam into electricity without combustion. Water and CO2 are also produced.

The drawbacks of SOFCs have historically included high upfront costs, high maintenance costs, and material degradation and durability issues. Given those challenges, where were square hole opportunities found?

Bloom Energy, now a $1 billion revenue company, achieved strong traction with customers that highly value uninterrupted power. Think data centers, hospitals, manufacturing, and biotech/pharmaceutical facilities. Offering technology that provides superior power quality, they also found demand among organizations with sensitive equipment that couldn’t tolerate power quality and voltage issues from the grid.

Bloom Energy also overcame SOFCs’ drawbacks by offering power purchase agreements (PPAs) that eliminated upfront costs and provided predictability of electricity cost, and by finding customers that valued the reduction of GHG emissions and near-elimination of air pollution compared to traditional power sources. Although SOFCs do produce some emissions when using natural gas as a fuel, they reduce emissions by ~33-45% relative to the marginal electricity produced on the grid. [4] The company has also gained traction in South Korea and Japan due to those countries’ demand for resilient clean energy solutions.

Electric school buses: Blue Bird Corporation

Blue Bird Corporation is a long-time player in the US school bus market, and now a leader in electric school buses. Although EV technology has drawbacks for some uses, Blue Bird found the school bus market a strong fit for the technology because those drawbacks matter less in that market.

While there are significant upfront costs for an electric bus fleet – including both the vehicles and the build-out of the charging infrastructure – long-term cost savings help offset them. Electric buses have operating cost advantages over traditional diesel buses thanks to the lower cost of electricity versus fuel and the reduced need for maintenance (fewer moving parts and no oil changes). Federal and state incentives, like those from the EPA’s Diesel Emissions Reduction Act and Clean School Bus Program, have made Blue Bird’s electric buses even more competitive. Additionally, new above-ground approaches to charging infrastructure have reduced the cost and time to build.

The reduced driving range of EVs is also less of a challenge, given school buses drive an average of only 32 miles per shift [5] and typically have a place to charge after each one. Their predictable schedules make it easy to ensure sufficient battery charge and to optimize charging over time, while providing the possibility to monetize energy flexibility via vehicle-to-grid configurations. Further, school districts can install solar panels at bus depots to make their power consumption even cleaner and lower cost. Add in the appeal of reduced air pollution, especially for urban school districts, and this market has taken flight for Blue Bird.

Prioritizing Future Square Hole Opportunities

It’s critical to remember that finding a square hole for your clean energy innovation is not a one-time effort.

Naturally, not all prospective customers will adopt your technology simultaneously. So, the best strategy is often to begin by targeting a niche segment where your product can solve a compelling problem. Once it becomes successful in that segment, you can leverage this success in adjacent market segments, knocking them down with a domino-like effect.

The key is to make sure the segments you target are related to the ones you’ve already knocked down. Doing so enables word-of-mouth communication, case studies, and other awareness activities to support your expansion from one segment to the next. Like a cyclist drafting off a teammate, you minimize drag and maximize speed by not having to start from scratch every time you enter a new segment.

Buyers in adjacent market segments often have similar problems, and customers within a niche segment are a better reference for prospects within that segment. For example, for a company providing solar-powered lighting for parks and wildlife areas, the Colorado Parks and Wildlife agency would be an ideal reference for the same agency in Utah. But if you are offering technology for construction sites, then a manufacturing or mining company might be a better reference.

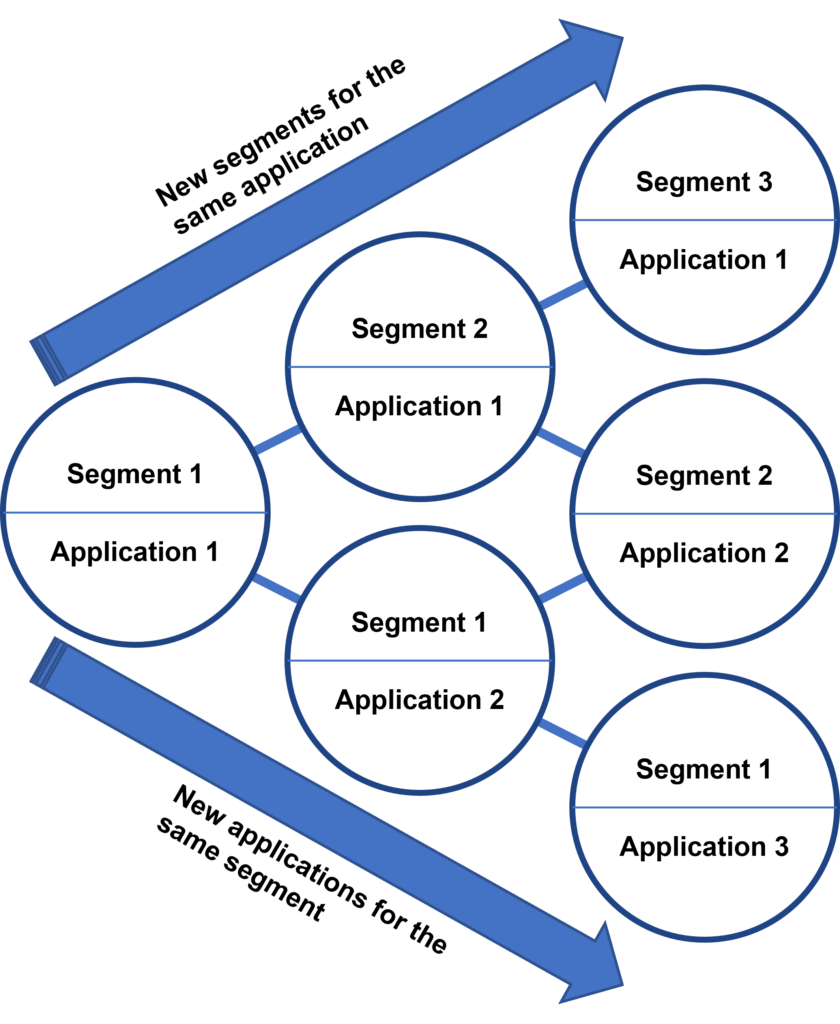

These shared characteristics and relationships can be mapped in a two-dimensional diagram called a proximity map of adjacent segments. Adjacent market segments share common characteristics in application requirements, relationships, and the market ecosystem.

A proximity map depicts adjacent segments so you can visualize a market penetration strategy in terms of targeting adjacent segments by taking advantage of their common requirements and relationships.

The most effective strategy for leveraging the success gained from winning your first niche market is making a careful choice regarding your next market-development step. This maximizes the chance of success and minimizes your business risk. The two alternatives are: (1) take a new offering to your original target market, or (2) take the same offering to a new market segment.

Companies with an emerging clean energy technology should try to avoid jumping in 2 dimensions at the same time (marketing a new product to a completely new target segment). And to harness the power of adjacency, avoid taking a horizontal approach in which you attempt to serve virtually any segment, even those with no connection to your first successful niche market.

We recommend a careful selection process in which you apply at least as much discipline in identifying your second niche market as you took in selecting your first. By successfully marketing to a second (and then third) segment of buyers, clean energy companies can expand their market presence by linking niche segments together under one umbrella theme. In the future you might even establish this as a recognized category.

Framework for Identifying and Capturing Square Hole Opportunities

Iteratively pursuing the following steps can help you find the best-fit segments for your technology:

- Identify core strengths and weaknesses

Put yourself in the shoes of an impartial observer and rigorously evaluate your technology’s current capabilities and drawbacks, as potential customers would perceive them. Don’t be overly critical, but also don’t gloss over legitimate concerns. Consider enlisting an industry friend or external consultant to give you an unbiased assessment if needed.

- Define potential market segments

Brainstorm dimensions of segmentation that could be relevant to your business.

- Example dimensions for clean energy startups: use case, operating conditions, geography, type of customer, size of customer, technologies used, deployment size, capex/opex needs, purchasing/financing needs, regulatory factors, supply chain factors, grid location/constraints

- Assess and prioritize segments

Quickly evaluate the dimensions, select the ones you believe matter most, and form working hypotheses about specific segments’ attractiveness.

- Example evaluation criteria (“Which customers would…”): receive the most value from your technology, care least about its drawbacks, buy most quickly, have highest willingness-to-pay, and provide the best opportunities for referral and public advocacy

- Learn rapidly and refine focus

Speak with potential customers in the segments that seem most promising. Try to confirm or disprove specific hypotheses. Pursue pilots where possible, and use every customer interaction to sharpen your understanding of the opportunity. The primary goal at this stage is rapid learning about who to target, what to build, and how to position and sell to them.

- Plan and execute market expansion

As you achieve product/market fit with your first segment, use the proximity map to help evaluate adjacent segments. If you can maintain an organizational commitment to continuous learning from market feedback, you have a key building block for long-term success.

The journeys of these companies show that success often comes from finding the square hole – a market where your technology’s strengths match perfectly with customer needs, and where limitations don’t hold it back. By focusing on the right opportunities – as First Solar did with utility-scale projects in hot locales – clean energy businesses can build a solid foundation, generate early revenue, and create a path to broader market expansion as their technology evolves.

This strategic focus isn’t just helpful – it’s essential. It enables startups to get the most out of their limited resources, refine their offerings with real-world feedback, and establish credibility in the marketplace. The takeaway is clear: don’t force your square peg innovation into a round hole market. Instead, search for or create the square holes where your technology is valued and cheered.