The Top Six Areas of Crossing the Chasm Confusion

Sadly, this research project reveals that 90% of the top-ranked, chasm-focused articles, blog posts, essays and book reviews on the Internet contain at least one of the errors or mistakes listed below. And most of these popular sites contain multiple errors.

I’ve also attempted to get everyone back to a basic level of understanding by explaining each mistake and correcting them.

1. Mischaracterizing an innovation

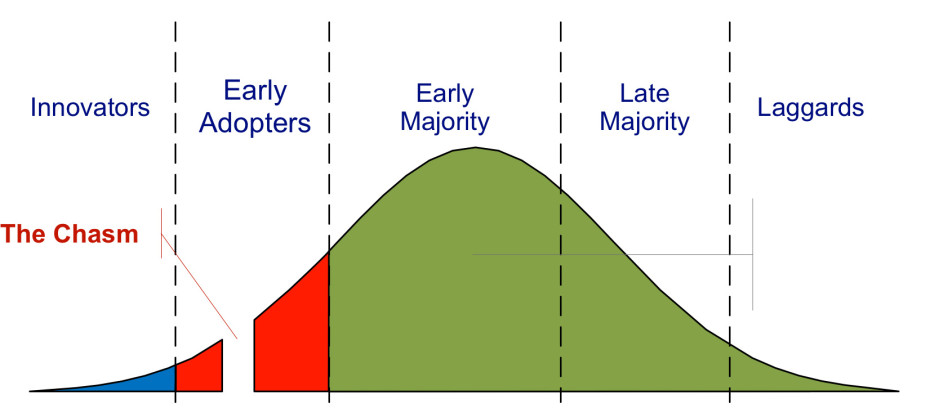

Many articles incorrectly state “every innovative product starts as a great idea that attracts innovators and early adopters.” In reality the starting point of an innovation is determined by the category of the new product, idea, method or concept.

And there is a big difference between a novel innovation (i.e. something no one has ever seen before) and a simple refinement. In fact, the majority of all new products are refinements, which implies they are already in the mainstream, and there is no chasm.

This issue was made even worse when the phrase “disruptive innovation” arrived on the scene in 1997. (see Source of Confusion #3 above)

2. Believing the chasm only applies to startups

The chasm concept offers decision-making guidelines for investors, engineers, enterprise executives, business managers and entrepreneurs throughout the high-tech community.

It isn’t just for startups. Established companies or “incumbents” are able to develop novel innovations too.

The question to ask is: does a new product or innovation require a new experience, new understanding or new learning to be able to be used properly? If the answer is “yes” then there is a chasm and it doesn’t matter who created it.

3. Thinking that applications and technologies are the same thing

The innovation-adoption curve (with or without a chasm) only applies to applications, and NOT to technologies.

This mistake is spread by many sources, not just websites and articles. You’ve probably seen a headline that says “XYZ research company reports that AI is considered mainstream technology in most companies.” This is a full-scale misinterpretation of the innovation-adoption process.

Mainstream adoption is only valid if it is tied to a specific category or application. For example, if a majority of hospitals in a geographical area use remote patient monitoring (RPM) for diabetes patients, it does NOT mean that RPM has crossed the chasm. It means that only one application of RPM has crossed the chasm. Other applications of RPM must be evaluated individually.

Keep in mind that Diffusion of Innovations and the original innovation-adoption curve were based on a specific application: the “use of hybrid seed corn by farmers in Iowa.”

4. Assuming psychographics are static or people stay in one category

Perhaps the most persistent mistake is that authors describe psychographic profiles based on a single application. In reality, people do not stay in the same category of adoption.

Just ask my neighbor. He is an early adopter of electric vehicles, but a laggard when it comes to a biological innovation called the COVID vaccine (which he refuses to accept.)

This misunderstanding might come from the trendy, over-hyped use of “personas” that has plagued the high-tech sector for years. But there is no such thing as a person who is an early adopter of all new innovations. People self-select their adopter category for each new product or innovation they encounter.

Labeling a person or an organization as a known early adopter is a recipe for failure. Because it is always situation specific.

5. Applying chasm theory to low-cost consumer products

Chasm theory was originally developed to address the needs of emerging high-tech companies. And more specifically, it was created for high-risk or high cost technology-based products that require new learning or a change in behavior.

Any mention of low-cost consumer items crossing the chasm indicates substantial confusion and misunderstanding.

6. Assuming chasm theory applies equally well in all industries

Chasm principles are more difficult to apply in certain industries, such as renewable energy and cleantech. The psychographic sequence that is the foundation of the chasm concept (innovator – early adopter – early majority – late majority – laggard) can be substantially skewed by government or utility programs designed to encourage or accelerate adoption

And in some cases, government subsidies or programs completely overwhelm the innovation-adoption process. A comprehensive, subsidized program can reduce the perception of risk to such a degree that mainstream customers adopt before they normally would in a purely commercial setting or market.

On top of the inherent difficulties of measuring localized, psychographic behavior, you must factor in the effect of public policy and incentives, which act to completely alter market dynamics.